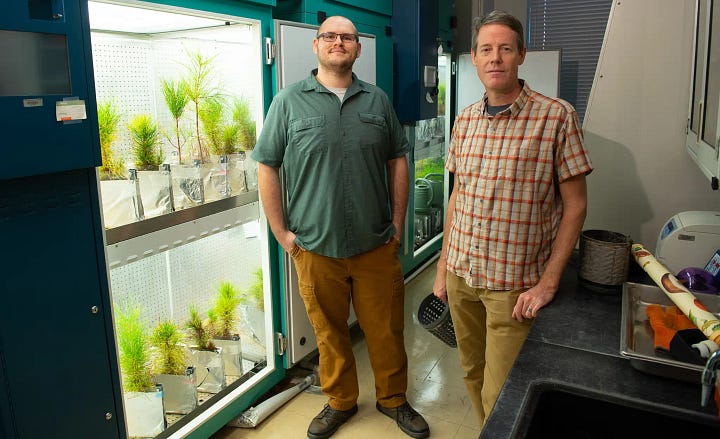

My guests today, Dr. Justine Karst, mycologist at the University of Alberta and Dr. Jason Hoeksema, professor of biology at the University of Mississippi, take us deep into the complex world of fungi, trees and the story we all might be getting wrong about their relationships. For a while now, there has been this narrative out there about trees communicating with each other through fungi. I’m sure you’ve heard of it. It’s a cool concept. Trees using the vast network of underground mycelium to not only communicate, but share and transfer resources and warn each other of dangers like bark beetle and wildfire.

It paints a visual of individual trees connected in a vast, sprawling network of entangled intelligence, altruism and shared wisdom. Kind of gives you this warm and fuzzy feeling. This concept is largely known as the “wood wide web” and if you’d asked me about it a few months ago, I would’ve been eager to tell this tale myself. Look anywhere and you’ll see article after article after podcast after book after popular culture reference of its existence as settled science. But what if I told you that this theory is far from having any semblance of scientific concensus, and not only that, but the evidence we have for it, might be a simplification of what’s actually going on.

Let’s start with the basics. The narrative of the “wood wide web” hinges on the relationship between trees and fungi, specifically mycorrhizal fungi. These fungi can form mutualistic associations with trees, connecting with their roots and extending a network of mycelium (the main body of the fungus) throughout the soil. The tree provides the fungi with carbohydrates it produces through photosynthesis (because fungi cannot photosynthesize themselves), and in return, the fungi can assist the tree with nutrient and water uptake.

This mutualistic relationship has been well-documented and is largely agreed upon within the scientific community. But where Justine and Jason feel we need to pump the breaks and gather more evidence, is in the interconnectedness and level of sophistication in communication and resource sharing proposed by the "wood wide web" theory. For many researchers, the primary function of mycorrhizal networks is to provide resources to individual trees, not necessarily to create a cooperative network of trees in a forest.

“I wish I would’ve caught it a lot earlier. But the only reason I started paying attention is because the claims got so crazy, and so incredible and so extraordinary.”

Several studies supporting the "wood wide web" theory are based on experiments under controlled laboratory conditions, a limitation that may not accurately represent the more complex and competitive conditions in a natural forest ecosystem. Basically, there’s just so much that we have yet to understand about these forest and mycorrhizal systems that Justine and Jason believe require much more evidence and experimentation for some of these popular claims to be substantiated and reach scientific consensus.

Moreover, while this concept of the “wood wide web” paints a romantic picture of the forests around us, this narrative might actually be oversimplifying the complexity of soil ecology and presenting the public with limited information that lacks evidence. The reality is, it’s just one of many possible interpretations of the evidence. The truth of soil ecology and tree-fungi relationships is likely more complex and nuanced, influenced by a myriad of factors we are just beginning to comprehend. So let's continue to explore, question, and learn about the awe-inspiring world beneath our feet, embracing its complexity and continuing to dig deeper into its mysteries.

Anyway, I learned so much from Justine and Jason on this episode, and I hope you do too!

-Sarinah

Resources:

https://olemiss.edu/hoeksemalab/jdh_papers.html

https://undark.org/2023/05/25/where-the-wood-wide-web-narrative-went-wrong/

Share this post